A Month in the Wilderness (Alone)

The clearest way into the Universe is through a forest wilderness.

— John Muir

I recently returned from five consecutive weeks in the wilderness, alone, with nothing but my large format camera and my own thoughts. Idaho, Wyoming, Montana, Colorado, Utah, Washington - chasing light and fall color across six states.

People pay good money to sit in silence retreats. I went into the wilderness instead. It changed me.

The first week was the hardest. Your mind, suddenly freed from Slack notifications and meetings, does something unexpected: it explodes. Thoughts you never knew you had come rushing up. There is no one to talk to, no one to process with. Just you, the cold morning air, and whatever your brain decides to surface. You resist it at first. Then you stop resisting.

This is what I woke up to on my first morning in Grand Teton. Freezing. Beautiful. A reminder that discomfort and reward often arrive together.

Why Slow Is a Feature

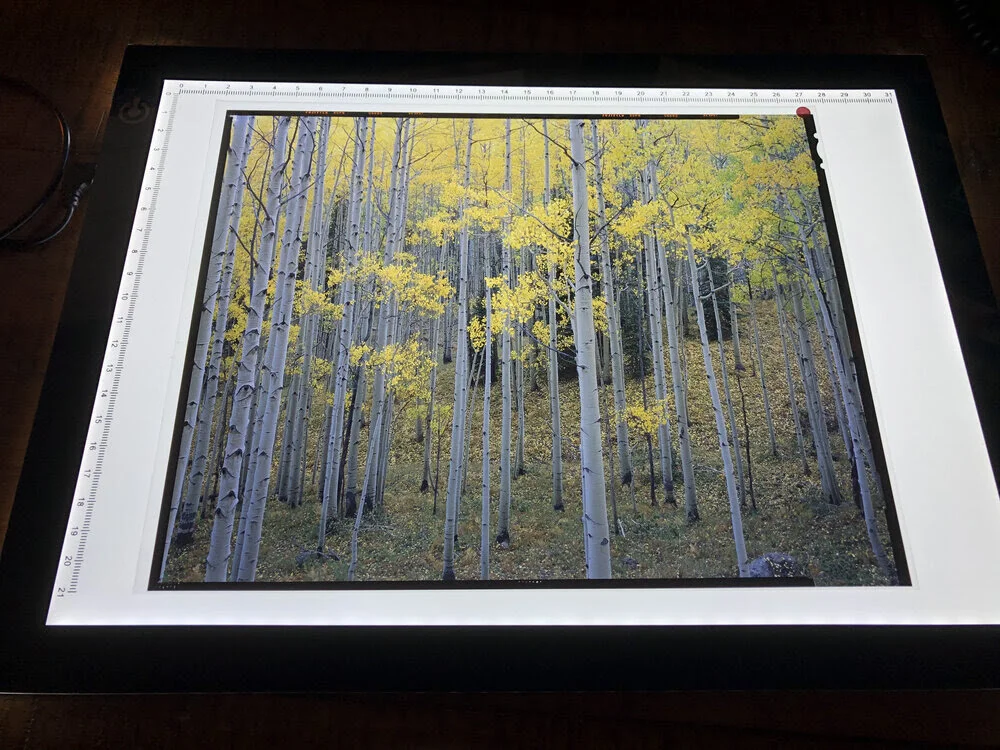

I shoot 8x10 large format film. Each sheet costs money. Each shot requires deliberation - setting up a heavy camera, composing under a dark cloth, metering light, calculating exposure. There is no spray-and-pray. No chimping at a screen to see if you got it.

This constraint is the point.

Slow forces you to see with your eyes instead of relying on screens. It forces presence - something almost impossible to achieve in our overstimulated lives. You develop a deeper connection with your subject because you have no choice. You must observe, wait, and commit.

This is how I approach complex projects now. How I think about building products. Deliberation is not inefficiency. It is craft.

The Week I Kept Showing Up

In Yellowstone, I found a spot along the river with extraordinary potential. I returned to it every morning for almost a week. Most days, the conditions refused to cooperate. Flat light. Wrong clouds. Nothing.

But I kept showing up.

One morning, everything aligned. The fog lifted off the water in layers, the light went ballistic, and I made what became one of my favorite photographs. The next day, I returned to the same spot just to confirm what I already knew: the moment was gone. Even if I wanted to, I could never repeat that shot.

This is the liminal truth of landscape photography - and perhaps of anything worth doing. You cannot manufacture magic. You can only show up, again and again, prepared and present, until the moment decides to reveal itself. And once it does, it is gone forever. There is no going back.

The Dangerous Spot

At Yellowstone Canyon, I climbed down to a spot I probably should not have reached - slippery snow, precarious footing, the kind of place where a wrong step has consequences.

But people also die falling off couches.

Standing there, I realized I was likely the only person who had ever photographed from that exact vantage point. The effort to explore, to go beyond the marked trail - it paid off. Not just with the image, but with the lesson: the extra mile is rarely crowded.

I carry this into everything now. Building a company. Making career decisions. The willingness to explore where others will not is often the difference between ordinary and exceptional.

Being Last

On my final days, I camped in Mt. Rainier as one of the last visitors before the park closed for the season. There was something romantic about it - melancholic, even. Knowing I shared that experience with perhaps a handful of people still scattered somewhere in the park.

I love this feeling. It usually means I am witnessing something fleeting, something most people will never see because they left too early or never came at all.

On my drive over Mt. St. Helens pass, I stumbled upon a scene transformed overnight by a dusting of snow. I spent an hour photographing it. When I finished packing my camera, the snow began to melt. Another unrepeatable moment, captured only because I was still there when others had already gone home.

What the Wilderness Teaches

Five weeks alone recalibrated something in me. The internal feeling about a subject at a specific moment - that should be the driver. Not the chase of some imaginary perfect image that may never exist. In pursuing the imaginary, you miss what is actually in front of you: something unique, authentic, and impossible to repeat.

In nature, there is no bad weather. Only conditions you choose to accept or reject.

Stay open to what presents itself. Show up repeatedly. Go further than comfortable. And when the moment arrives, be present enough to recognize it.

There is no going back. There is only now.